The effectiveness of imagery as an aid in free recall

Introduction to the Reserch

The relationship between imagery and memory has long fascinated psychologists, yet the evidence available is somewhat inconsistent. Interest in imagery and its effects on memory was revived in the 1960’s by psychologists such as Allan Paivio and Gordon Bower. They found that when participants were instructed to link items together through images, their recall was considerably improved. They also discovered that highly imageable words, such as concrete nouns were easier to recall than words of low imageability such as abstract nouns, however, the work of some researchers, (Sheehan, 1971, Shaughnessy, Zimmerman and Underwood, 1972, Richardson, 1972) contested these findings.

The work of Morris and Stevens (1974) set out to investigate the inconsistencies in the evidence. They set out to investigate whether recall is facilitated only when the images which are formed link together the items, and also whether there is any difference between the participants who are instructed to form a singular image, and the control group who are given no instructions regarding imaging. The results of their experiment supported their first hypothesis, and indicated that there was no difference between the control and the singular image group.

If imagery improves recall in memory tasks then what is it about the imagery that facilitates this? Morris and Stephen (1974) proposed four different ways in which this effect would be achieved. Firstly, and perhaps most obviously is that imagery provides a means of connecting and organising unconnected material. Secondly imagery may enhance the ‘distinctiveness’ of an item, thus rendering it more memorable. Thirdly, storing the item as both a visual and a verbal memory may aid recall. Finally, it may be easier to retrieve memory from a visual store than from a verbal store. The results of Morris and Stephen’s (1974) experimentation appears to suggest that only the first factor, the connecting and organising of items has any effect on improving memory, as the participants in the single imagery group did not score any higher than the control group, a t-test confirmed this, t (36) = .19, p>.8.

In his famous article, “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus two.” Miller (1956) demonstrated how chunking can be used to expand the limited capacity of short-term memory. Gross (2005) describes chunking as, “involved whenever we reduce a larger to a smaller amount of information.” (246) This not only increases the capacity of short-term memory but also acts as a form of encoding, as meaning is imposed on otherwise meaningless material. Does imagery therefore assist the participant in chunking the items into related groupings?

What this piece of research has done....

This experiment attempts to replicate Morris and Stephen (1974) using a different word list and length, which incorporates both moderately imageable words and highly imageable words, which is an expansion on Morris and Stephen. (1974) As their exact instructions were not reported, those given to the participants in this experiment may vary somewhat. The researchers aim was to discover whether imagery as a study strategy facilitates free recall of words when words are imaged independently of one another, and whether the benefits of imagery are limited to words that are highly imageable.

The complex inner workings of the brain

Method

The experiment employed a mixed factorial (or split plot) design. The dependant variable is the amount of words recalled by the participant. The independent variable tests two factors. The first was the instructions given to the participants, which was manipulated between groups on three levels, the instructions were randomly allocated. The first set of instructions guided the participant to recall as many words as possible, without mentioning the use of imagery, this constituted the control group. The second set of instructions encouraged the participants to form a mental image for each word, and the final set of instructions asked the participant to link the images together in groups of three. The second factor of the independent variable is imageability of the words, which was manipulated within participants, and was tested on two levels, moderately imageable words and highly imageable wordsThe experiment employed a mixed factorial (or split plot) design. The dependant variable is the amount of words recalled by the participant. The independent variable tests two factors. The first was the instructions given to the participants, which was manipulated between groups on three levels, the instructions were randomly allocated. The first set of instructions guided the participant to recall as many words as possible, without mentioning the use of imagery, this constituted the control group. The second set of instructions encouraged the participants to form a mental image for each word, and the final set of instructions asked the participant to link the images together in groups of three. The second factor of the independent variable is imageability of the words, which was manipulated within participants, and was tested on two levels, moderately imageable words and highly imageable words

participants

ParticipantsThe participants were one hundred and forty one undergraduate and Graduate Diploma psychology students from the University of Bolton. See appendix B for full results of each participant.

Materials

The wordlist presented to the participants was made up of sixty nouns from the Toronto Word Pool (Friendly, Franklin, Hoffman and Rubin, (1982). The list comprised thirty high imageability nouns (e.g.: mirror) and thirty moderately imageable nouns (e.g.: justice). The confounding variable of frequency, that is how often the words are used in our language, was controlled for, as high frequency words are better recalled than lower frequency words (Hall, 1954). Kucera and Francis (1967) determined norms for word frequency. Words of high frequency were deemed (>200) and low frequency (<25) per million, so high frequency words were emitted, and the two groups of selected words were matched for word frequency, with means of 73.7 and 73.8. See appendix A for a list of the words used.

The wordlist presented to the participants was made up of sixty nouns from the Toronto Word Pool (Friendly, Franklin, Hoffman and Rubin, (1982). The list comprised thirty high imageability nouns (e.g.: mirror) and thirty moderately imageable nouns (e.g.: justice). The confounding variable of frequency, that is how often the words are used in our language, was controlled for, as high frequency words are better recalled than lower frequency words (Hall, 1954). Kucera and Francis (1967) determined norms for word frequency. Words of high frequency were deemed (>200) and low frequency (<25) per million, so high frequency words were emitted, and the two groups of selected words were matched for word frequency, with means of 73.7 and 73.8. See appendix A for a list of the words used.

Procedure

The participants were randomly allocated into one of the three different groups, the control, the single and the triple imagery group. They were asked to read the instructions and follow them carefully. The first list of presented words contained the moderately imageable words. Each word was presented for five seconds, with a one second gap after every third word. After the first list there was a ‘distracter’ test, which lasted about two minuets and involved ordering sets of numbers from lowest to highest, which prevents rehearsal. The participants were then asked to recall as many words as they could. Then the same process was repeated for the second word list, which contained the highly imageable words. At the end the participants were all debriefed. The results obtained were then collected and entered into SPSS ready for statistical analysis.

results

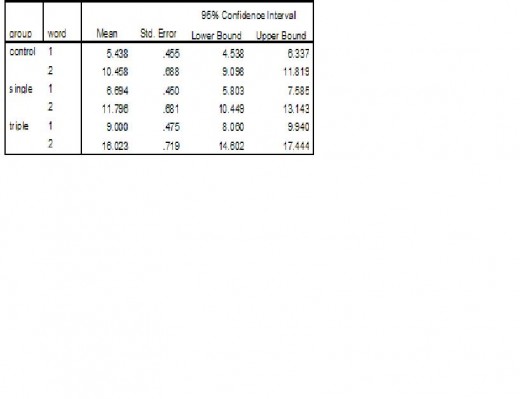

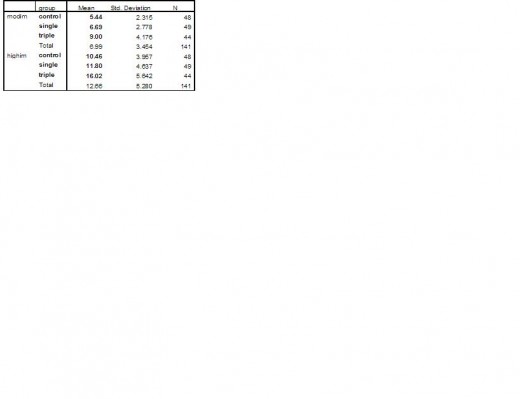

The first part of the experiment investigated whether the use of imagery as a study aid significantly increased word recall, was there a significant effect on the between groups factor of imagery instructions between the control, the single and the triple imagery word group? An ANOVA test was conducted to analyse the results, and reported a significance at F = (2,138) = 19.54, p < 0.001) Initially looking at the descriptive statistics the means appear to demonstrate a higher recall on moderately imageable words in the triple group, 9.00 compared to the single image group 6.99. The mean of the control group was 5.44. On the high imageability word list the pattern continues with the triple group recalling a mean of 16.02, the single image group recalling 11.80, and the control 10.46.

results continued..

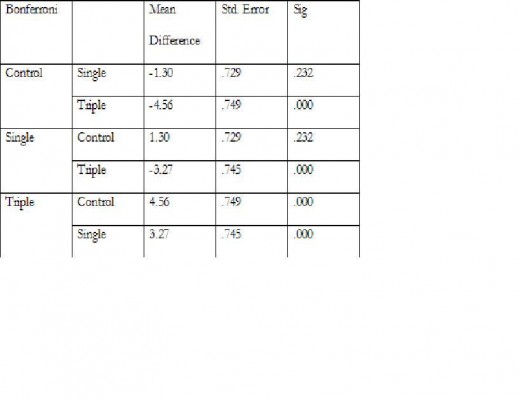

Conducting multiple post hoc tests reveals the significance of the results. Bonferroni demonstrates that there was no significant difference between the control group and the single group .232, but there was a significant difference between the control and the triple imagery group, and between the single and the triple group.

spss output table

results continued...

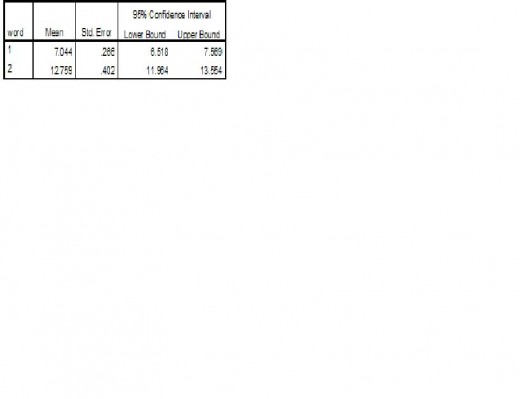

These results appear to confirm the initial hypothesis, that imagery as a study aid does indeed improve recall. The results also show that there was no significant difference between the control and the single imagery group, indicating that it is the linking of similar images which improves memory. The second part of the experiment looked into whether there was a significant difference between the recall of moderate imageability words and high imageability words. This was the within groups factor. An ANOVA test reported a significance as F=(1,138) = 332, p < 0.001. The mean of recalled words for the moderately imageable words is reported as 7.044 while the highly imageable words is 12.759, indicating that highly imageable words are recalled more easily. The statistics demonstrate that across all three groups, highly imageable words are better recalled than lower.

table (content from SPSS)

Discussion

The results obtained demonstrate a significant main effect between imageability and word recall, and also demonstrate that highly imageable words are more memorable than moderately imageable words. The results also confirm Morris and Stephen’s (1974) findings that there was no significant difference between the control and the single imagery group, indicating that it is the linking of similar images which improves memory. If imagery improves recall in memory tasks then Morris and Stephen set out to discover what is it about the imagery that facilitates this. They proposed four different ways in which this effect would be achieved and their experimentation supported their initial view, that imagery provides a means of connecting and organising unconnected material. The results of this experiment appear to support this, as there was no significant difference between the control group, who used no imagery techniques, and the ‘single’ imagery group. It was only the triple imagery group, who were instructed to link the items together, that appear to benefit from the use of imagery. There is however an important point to be made, the partial eta squared shows the percentage that a particular factor is responsible for the outcome. The multivariate tests demonstrate that in the experiment the particular words used for responsible for .706 so 71% of the recall, whereas the word and group interaction was responsible for only 0.57, so 6% of the recall. This appears to demonstrate that it is in fact the particular word used, and its imageability, which determines recall. Typically in order to conduct parametric tests homogeneity of variance must be established. This indicates that the variance between each group is similar, and can be assessed in repeated measures factor ANOVA’s by Mauchley’s Test of Sphericity. Sphericity can be assumed when the score is <0.05, in this experiment the score was 1.00, so Greenhouse-Geisser was conducted to adjust the degrees of freedom and control for the violation. The F value was reported as the same for the Greenhouse-Geisser test, and for when sphericity is assumed, so this factor would not have impeded the research. One potential fault with this piece of research is that although the participants were given specific instructions to follow, they may have chosen to ignore them and to instead use their own techniques and methods, which would interfere with the experiment. The participants were all psychology students with some understanding of memory and cognition, and therefore they may have been familiar with certain memory enhancing techniques, and notions of ‘chunking’. If the experiment were to be done again it may be beneficial to use a random sample of the population rather than a specific demographic group. When asked to recall the words, some participants experiences ‘intrusions’ that is, the recollection of words that were not on the original list. It may be interesting to examine these intrusions in future experimentation. It may also proof informative to examine how participants respond if the words are presented to them aurally rather than visually on a computer screen, as was the case in this experiment. The aural presentation may involve different stages of encoding and thus lead to a difference in recall. The results obtained demonstrate a significant main effect between imageability and word recall, and also demonstrate that highly imageable words are more memorable than moderately imageable words. The results also confirm Morris and Stephen’s (1974) findings that there was no significant difference between the control and the single imagery group, indicating that it is the linking of similar images which improves memory. If imagery improves recall in memory tasks then Morris and Stephen set out to discover what is it about the imagery that facilitates this. They proposed four different ways in which this effect would be achieved and their experimentation supported their initial view, that imagery provides a means of connecting and organising unconnected material. The results of this experiment appear to support this, as there was no significant difference between the control group, who used no imagery techniques, and the ‘single’ imagery group. It was only the triple imagery group, who were instructed to link the items together, that appear to benefit from the use of imagery. There is however an important point to be made, the partial eta squared shows the percentage that a particular factor is responsible for the outcome. The multivariate tests demonstrate that in the experiment the particular words used for responsible for .706 so 71% of the recall, whereas the word and group interaction was responsible for only 0.57, so 6% of the recall. This appears to demonstrate that it is in fact the particular word used, and its imageability, which determines recall. Typically in order to conduct parametric tests homogeneity of variance must be established. This indicates that the variance between each group is similar, and can be assessed in repeated measures factor ANOVA’s by Mauchley’s Test of Sphericity. Sphericity can be assumed when the score is <0.05, in this experiment the score was 1.00, so Greenhouse-Geisser was conducted to adjust the degrees of freedom and control for the violation. The F value was reported as the same for the Greenhouse-Geisser test, and for when sphericity is assumed, so this factor would not have impeded the research. One potential fault with this piece of research is that although the participants were given specific instructions to follow, they may have chosen to ignore them and to instead use their own techniques and methods, which would interfere with the experiment. The participants were all psychology students with some understanding of memory and cognition, and therefore they may have been familiar with certain memory enhancing techniques, and notions of ‘chunking’. If the experiment were to be done again it may be beneficial to use a random sample of the population rather than a specific demographic group. When asked to recall the words, some participants experiences ‘intrusions’ that is, the recollection of words that were not on the original list. It may be interesting to examine these intrusions in future experimentation. It may also proof informative to examine how participants respond if the words are presented to them aurally rather than visually on a computer screen, as was the case in this experiment. The aural presentation may involve different stages of encoding and thus lead to a difference in recall.